Muscle cramps, responsible for leaving their victims reaching for their toes on the sidelines of a running race, to screaming in silence in bed at 3 am. So why do muscles cramp? Is there more we can do other than letting it pass or getting another massage/rub down? Do salt tablets actually work?

Muscle cramps are described as sudden, spasmodic, painful involuntary muscle contractions that last less than 60 seconds. Muscle cramps can occur as a symptom of a range of medical conditions, genetic causes, or exercise. In this blog, we will focus on exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMC) and discuss why they happen and what you can do about it!

EAMC is a relatively common condition and can affect anyone – whether you’re a weekend warrior or an elite athlete, EAMC can be disabling. They can occur during or immediately after exercise, and although EAMC is generally short-lasting, they often reoccur if activity is continued at a similar intensity, having a direct negative impact on performance. EAMC most commonly affects the calf, hamstring, and quadriceps muscle groups respectively, and are often reported in endurance sports, such as ultra-marathons and triathlons. However, they are also common in AFL players, cyclists, and other sports where a rapid change in intensity is required (such as accelerating from a jog to a sprint). This is an important consideration when asking WHY EAMC occurs…

Why do cramps occur?

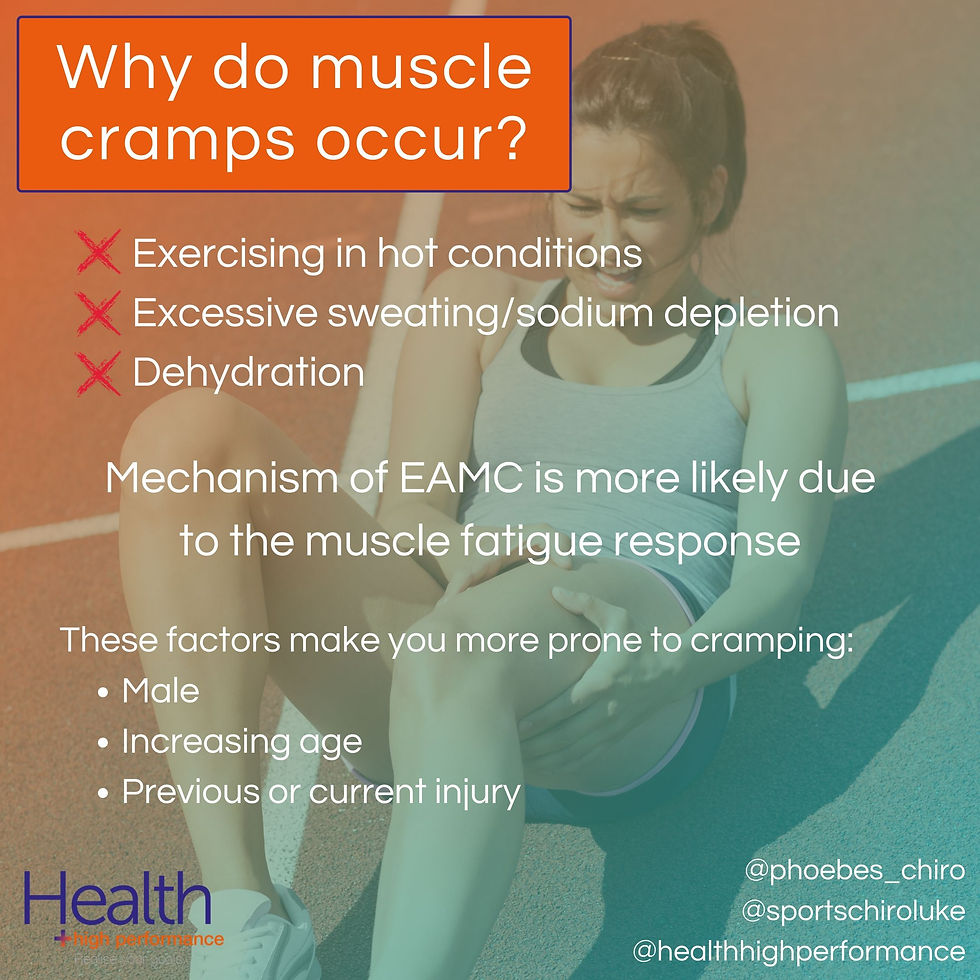

Historically, cramps have been blamed on dehydration, exercising in the heat, and electrolyte depletion, but these theories have now (mostly) been debunked. Recent research has helped us to understand that EAMC is more likely multifactorial and occurs due to the muscle fatigue response and abnormal neuromuscular control. Let’s take a closer look at what that all means:

EAMC is not caused by exercising in hot conditions. EAMC can occur in the heat, but can also occur in cold conditions. Additionally, cooling the body and localized muscle cooling during cramping has not been shown to relieve it.

Excessive sweating/sodium depletion/dehydration is not the predominant cause of EAMC. Studies have shown that athletes suffering EAMC were not dehydrated, nor did they show disturbances in serum electrolyte (sodium) concentration.

Low sodium concentration in the blood (hyponatremia) may be associated with generalized skeletal muscle cramping at rest (but not associated with EAMC). The mechanism of EAMC is more likely due to the muscle fatigue response

These factors also make you more prone to cramping:

Male (not much you can do to change this!)

Increasing age (again not much can be done here)

Previous or current injury: if the affected area is weak, then it may be more prone to fatigue and cramping- get this assessed!

So how does a fatigued muscle cause EAMC?

To understand this, it’s important to understand two basic principles behind how a muscle works:

Golgi Tendon Organ (located within a tendon): sense when a tendon is under tension. messages from the Golgi Tendon Organ inhibit (or stop) muscle activation.

Muscle Spindles (located within the muscle belly): detect the change in the length of a muscle – they signal muscles to contract

When a muscle becomes fatigued, it’s theorized that there is increased input from muscle spindles, but decreased input from Golgi Tendon Organs. Put simply, EAMC occurs when Golgi Tendon Organs cannot stop the over-activity of muscle spindles, causing the muscle to contract uncontrollably (and very painfully). Knowing about all this physiology is important because it can instruct us on how we can best treat and prevent EAMC.

What to do when you have a cramp?

Passive stretching is the most effective technique to provide symptomatic relief from a cramp. This is because when we stretch a muscle, we increase the Golgi Tendon Organ’s inhibitory role. Basically, stretching sends a message via our nervous system to stop a muscle from contracting. Stretching should be held for 10-20 seconds to initially stop the cramp. Some research suggests that keeping the muscle in a lengthened position for a period of up to 20 minutes is best to prevent the cramp from recurring (eg for a hamstring cramp, sit with the leg out straight in front of you)

Contracting the opposite muscle group can also provide immediate relief from a cramp eg. contracting the quadriceps (thigh muscles) for hamstring cramps, or ankle dorsiflexors (pointing ankle towards your head) for calf cramps

Massage can also help to stop a cramp. Although as with the above interventions, none will PREVENT it from happening again!

What about preventing them?

Strength & conditioning: Because the predominant cause of EAMC is fatigue, addressing general conditioning and improving endurance should be the priority for reducing EAMC risk. Ensure you have adequate strength in the appropriate areas! We utilize the AxIT system in our clinic to comprehensively assess your strength, click here to read more.

Plyometric and eccentric strength training has been shown to improve neuromuscular control, which may also reduce the risk of EAMC

Magnesium and salt tablets: as mentioned previously, sodium depletion & electrolyte disturbance is unlikely a contributor to cramping, so unsurprisingly there is low-level evidence for the use of magnesium and sodium supplementation to prevent EAMC. So you can ditch the salt tablets!

Pickle juice: This is becoming an increasingly popular remedy for cramping. Whilst 2 studies have shown a large improvement in cramping time by those taking pickle juice, there were NO changes in electrolyte levels, which further debunks the electrolyte imbalance causing cramps theory. So how does pickle juice work? Miller and his team suspect it may be the vinegar content that triggers a response in our throats, that then affects alters the activity of nerves (alpha motor nerve activity to be precise). So whilst pickle juice may be effective, plain vinegar might be just as effective, and small amounts may do the job to trigger the neural reflex! Also whilst pickle juice can help to RELIEVE a cramp, we don’t have evidence to show that it can PREVENT them

Recovery: despite it’s potential to help with muscle fatigue, it’s an area that hasn’t been thoroughly investigated for its effect on cramping. Sleep quality and stress levels are things that may contribute to fatigue.

So if recurrent cramping is something you suffer with, don’t hesitate to contact us to establish why they are occurring and take the appropriate steps to prevent them!

References:

Garrison SR, Allan GM, Sekhon RK, Musini VM, Khan KM. Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD009402. Published 2012 Sep 12. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009402.pub2

Miller KC, Mack GW, Knight KL, et al. Reflex inhibition of electrically induced muscle cramps in hypohydrated humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):953-961. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c0647e

Miller KC, Mack G, Knight KL. Electrolyte and plasma changes after ingestion of pickle juice, water, and a common carbohydrate-electrolyte solution. J Athl Train. 2009;44(5):454-461. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-44.5.454

Minetto MA, Holobar A, Botter A, Ravenni R, Farina D. Mechanisms of cramp contractions: peripheral or central generation?. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 23):5759-5773. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212332

Nelson NL, Churilla JR. A narrative review of exercise-associated muscle cramps: Factors that contribute to neuromuscular fatigue and management implications. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54(2):177-185. doi:10.1002/mus.25176

Schwellnus MP. Cause of exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMC)--altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion?. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(6):401-408. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.050401

Shang G, Collins M, Schwellnus MP. Factors associated with a self-reported history of exercise-associated muscle cramps in Ironman triathletes: a case-control study. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(3):204-210. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e31820bcbfd